Beliefs. They bring solace. They cause suffering. They unite us. And they divide us.

Sarah Krasnostein, author of the much-lauded The Trauma Cleaner, was curious about living in that cognitive space between “the world as we’d like it to be and the world as it is”.

What is it to have beliefs that exist on the fringes? And what, in this world of diverse beliefs, are our commonalities? What could bring us together?

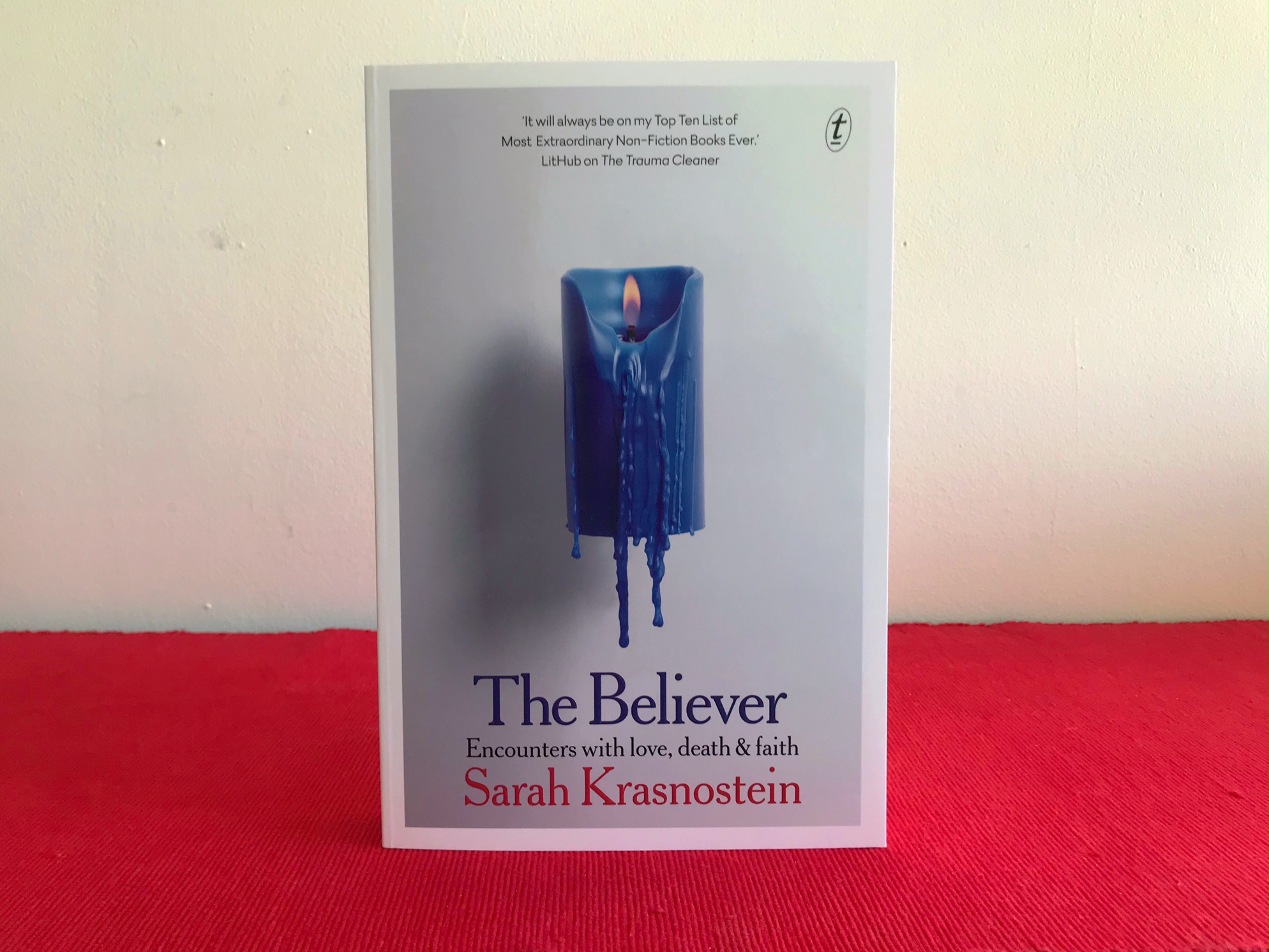

Krasnostein explores her questions through the lives of six people (and their communities) whose beliefs sit outside the mainstream of society in The Believer: Encounters with love, death and faith.

There’s death doula and Buddhist chaplain, Annie, who’s had a life-and-a-half of turmoil, assisting Katrina and her family through the final months of her life.

There’s Lynn, unjustly incarcerated for almost 35 years, and now living a life of service.

There are folks, with PhDs in science, who believe the earth was created in six days.

There’s a religious community, whose urban street choir transfixes the author on a hot Summer’s day, who are united in their beliefs of a punishing God.

There are adults who still recall the day an unidentified flying object was seen behind their suburban Melbourne school in 1966. Or those who believe the disappearance of a light aircraft mid-flight from Moorabin to King Island in 1978 was due to alien interference.

There are real-life ghostbusters.

You could read The Believer and come away scratching your head, thinking “People do think the darn’dest things”.

Or you could, like Krasnostein, look under the surface, for the commonalities. We may have vastly different experiences to the folks profiled in these pages but we know what it feels like to feel disappointed or afraid or vulnerable – or to belong or have purpose.

Over the course of writing The Believer, Krasnostein discovered that while beliefs may divide us, feelings unite us.

The beauty in Krasnostein’s writing is her respect for her subjects. Unlike others who report on “them” on the fringes, she doesn’t mock or undermine her subjects even though their beliefs differ from her own. Instead there is curiosity and a generosity that is admirable and sometimes a little uncomfortable.

I find a little discomfort in reading to be a good thing – it’s a little nudge for me to examine my own beliefs. It’s that unsettling feeling when you realise that you’re thinking “that’s quite reasonable” about a belief that is opposite to your own.

There were little nudges throughout The Believer – tiny challenges to my own way of seeing the world. For example, when Krasnostein is admiring certain aspects of Mennonite parenting, I thought “Oh now their beliefs make sense. They raise delightful children!” And then I remembered this is the same parenting that excommunicates and deems a sinner those who are different.

So, I don’t think any of my beliefs changed with these nudges but I did come away with a little bit of Krasnostein’s generosity for those who think differently to me.

I also came away from The Believer wanting to know more. (Annie and Lynn could easily have complete books written about them.) We get glimpses of resilience, of people finding their path in a foreign world – but I was curious as to what helped them keep the faith. How could they have such certainty in world of uncertainty? It’s an answer that would help many of us in our world of climate-deniers and business-as-usual misogyny and racism. Perhaps that’s the next book …

In a time when diversity and inclusion in our communities and work places is beginning to be valued, finding those connection points to live and work together is essential.

Krasnostein opens our eyes to our commonalities and begins a much-needed conversation about how we create a harmonious and inclusive society.

Let’s continue it …